evocative objects (ongoing)

An interest in how things relate to people has been persistent in much of my work. It expresses itself in part in a love of still life as a genre, in the broadest sense: a sense that incorporates work across multiple mediums, including writing. That is to say, in the work I make, there is always an implicit relationship between things and the actions that have taken place in, on or around them. Nouns, and the verbs that animate them; possibly, above all, gerunds.

If the plates, thimbles, scissors, keys and saltshakers that Pablo Neruda addresses in his Odes to Common Things speak of moments of sensory and affective caress, such objects also extend an invitation beyond that of perception and sensuality: an invitation to narrative. We use our evocative objects to keep re-engaging with the construction of our own stories. […] For a long time, I have been interested in such autobiographically charged objects: not so much heirlooms as things skimmed off the surface of everyday life. Things that furnish our day-to-day existence and that, in their acquaintance with the humdrum, act beneath the visible as spurs to memory, cues to thought. We may regard these as trophies or tokens: always, they are private memorials. Yet objects – like facts – can intrude into the fluid, ambiguous space of remembering. They might remind us of our old selves or of other people, but that very association may fossilise the living, changeable beings we once were, and those others whom we miss (from Second Chance: My Life in Things, published by Open Book, Cambridge, 2022).

Two short texts out of which two fuller essay chapters were subsequently constructed, were published as “Surviving Objects,” Life Writing Projects, University of Sussex, 2019.

The carousel of underwear that was hanging to dry in my mother’s bathroom at the time of her death in 2012. I have kept it precisely as it was then.

A folding Kamasutra that stood in the place of the lover who gave it to me, and who kept me at arm’s length.

My father’s hairbrush. I remember it applied to his wide, lustrous waves. He died in 1982.

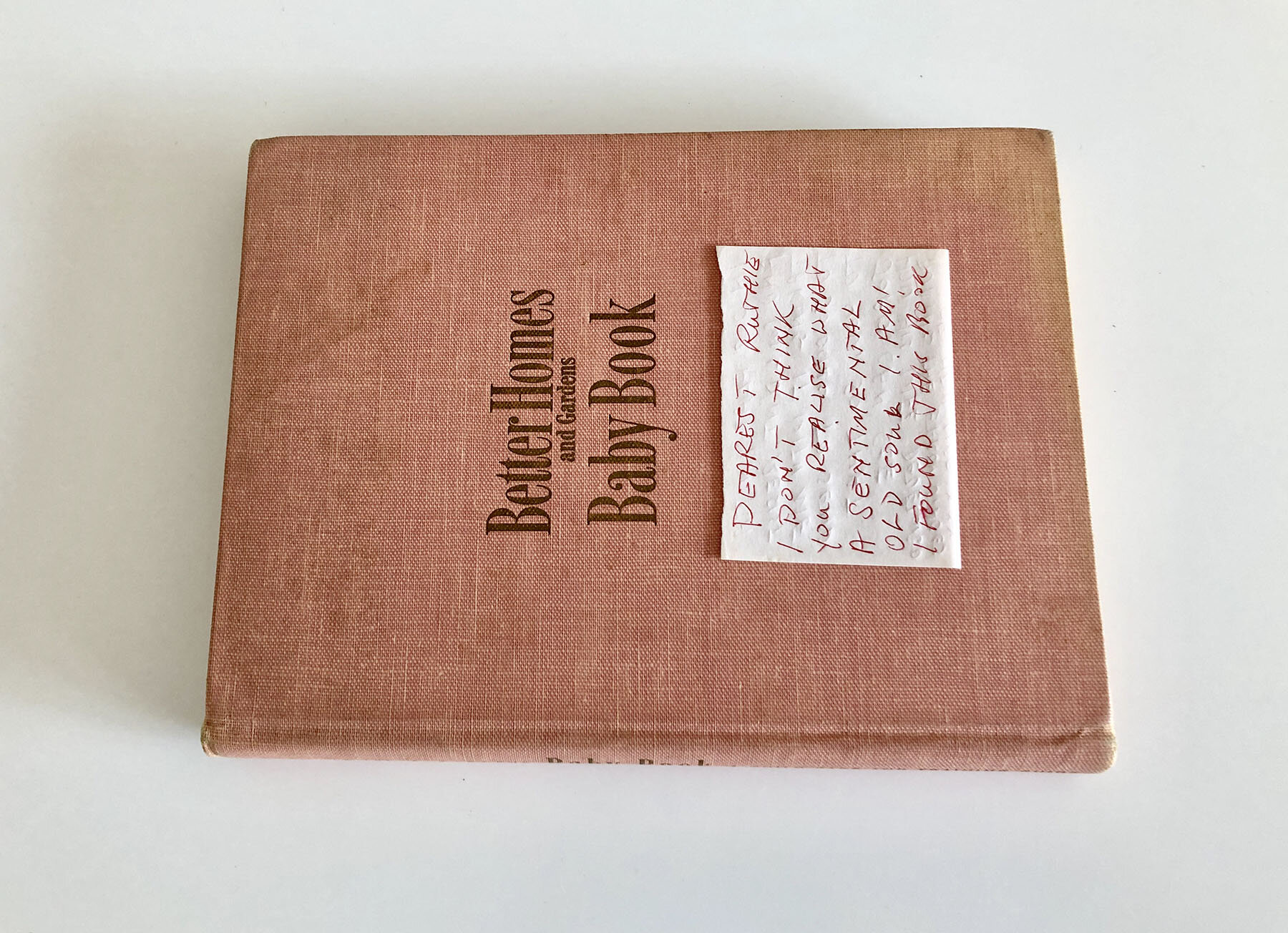

A book I won as a prize for improvement in piano playing when I was a child. Many years later, it was chewed by a beloved puppy, who arrived in my life in place of the baby that didn’t. How many temporalities does an object occupy?

My ponytail, severed when I was thirteen. My mother said I’d look good with my hair short, but I didn’t like it.

A table lighter containing, in its body of resin, a miniature seascape. It’s been in existence since I have. I remember or misremember my parents using it.

Letters from one lost love, re-encountered many years later as a friend.

My mother’s diary, used as a notebook/shopping list, found in the drawer of her bedside table at the time of her death in 2012.

I have, since 2018, been working on a series of interconnected essays about my evocative objects. You might think of such objects as keepsakes or mementos, since they are steeped in memory and narrative. Writing about these objects, like photographing them, becomes a way of keeping them, though “keeping” is itself double edged. Arguably, in holding onto something that once had a dynamic relationship with a person, you are enshrining it in a way that flattens out the distinction between vivification and mortificatio. As though embalming it. n this sense, such keepsakes are like photographs, which are often our most treasured mementos: things in which the past is preserved, even as its lived reality is deleted.

These objects inhabit our lives in complex ways. Purges might be followed by sprees of conservation. Through my own evocative objects, I have found a way of following threads of thought through the fabric of my own life; but more than that, I have also found inroads to books and works of art that I’ve loved, that I’ve treasured over the years. My dead husband’s table napkin, for example, on which I searched in vain for a stain – a precious trace of his once-having-been-alive – leads me to the stain on a table napkin in Heinrich Böll’s The Clown, a book I first read at sixteen and never forgot.

The year that I began photographing these objects, I also started photographing the remains of dog toys I’d kept long after the beloved pooch had died; kept precisely because in their gnawed, nibbled and eviscerated shapes, I always saw the imprint of the dogs I’d loved, their intense actions, their doggy occupations.

In 2011, I asked about twenty friends and acquaintances to bring me an object that was meaningful and evocative to them. I photographed these items without being quite sure what to do with those images. What interested me, perhaps more than the images, was the ceremony of bringing forth that all these people performed in laying out their objects before me. That was something I did not capture; and it is perhaps for that reason that I felt the need to write about evocative objects, rather than letting them exist only within the domain of the image. I have, however, remained persistently interested in the use of evocative objects by other artists and writers (watch this space). Nevertheless, it is the braiding together of words and images, their interdependence rather than the opposition they might establish, that remains central to my work in all mediums.

Liam: Dad, 2011

Monica: Cheng, 2011

Tom: Edgar, 2011

Debbie: George

Ann: William, 2011

Sid: Winifred, 2011

Sarah: Natalie, 2011

Els: Robin, 2011

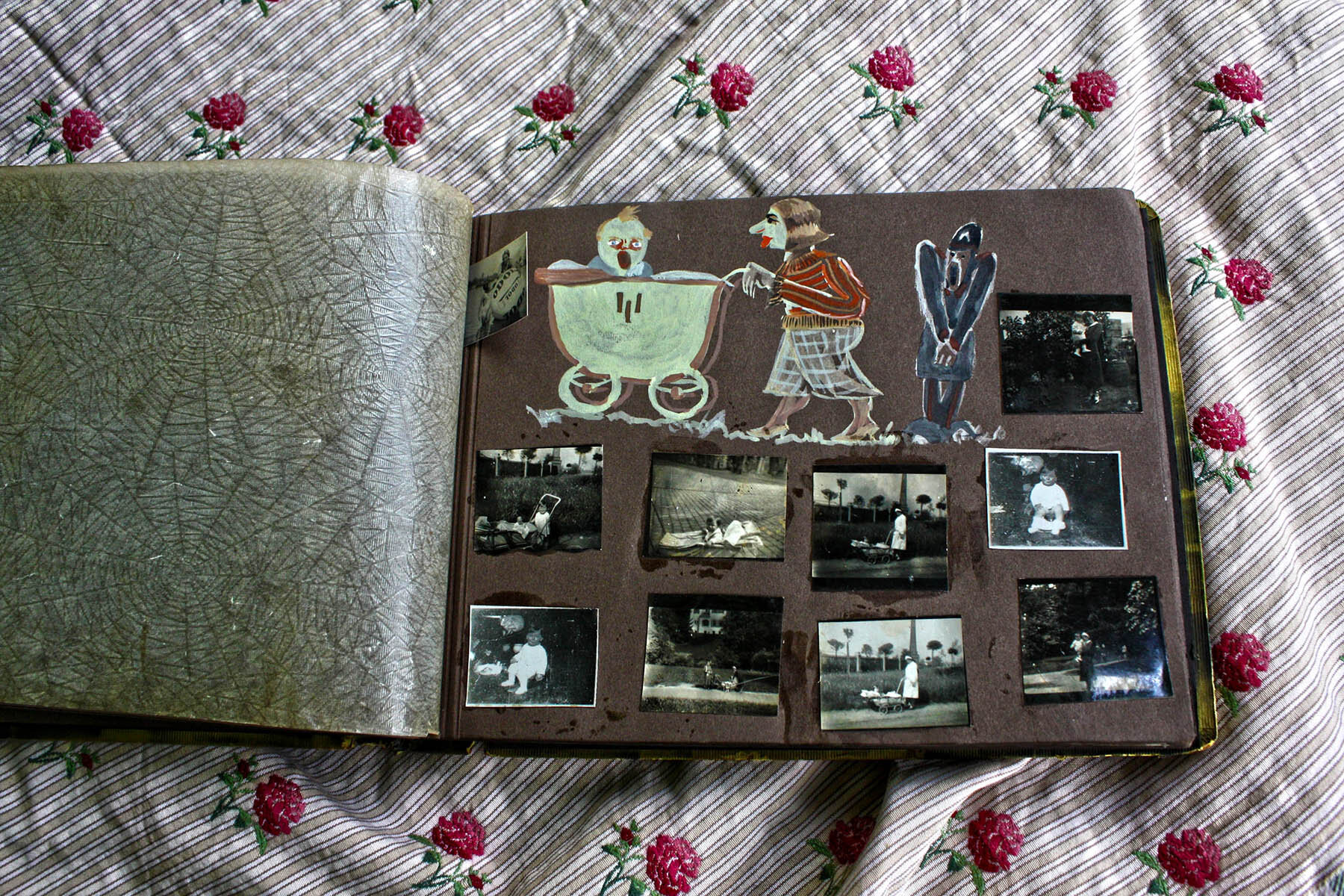

Ea: Oldemor, 2011

Jay: Jean-Pierre, 2011

A severed ponytail, a family album, a book, another book, a cigarette lighter, a hairbrush, a napkin in its ring, an old audio cassette, a chewed dog’s toy, a clumsy drawing, soiled pyjamas, an accordion-folded Kama Sutra, a photograph album, a pair of sunglasses, a pile of letters, a pair of shoes: these evocative objects are things that enable me to experience my self as I inhabit my particular world. Each object is a survivor, testifying to a period or a sequence of events in my past, and thus to my own survival as a narrator. They speak about the way I rub along, living in things, as Virginia Woolf succinctly puts it. […] Nevertheless, objects – even ones that are not charged with the burden of carrying our personal histories – have contours that are more porous than we might imagine. Their quiddity is not that assured. The self finds and defines, and then re-finds and re-defines itself in the process of assigning shifting mental and emotional places to and for things. Loved, unloved, loved again perhaps. We attach ourselves to objects because of their perceived stability: this ponytail, this handkerchief, this sled with the word Rosebud inscribed upon it. The very thingness of our evocative objects, their staunch assertion of presence, confers the fantasy of stability on the subject, on me (From Second Chance: My Life in Things, work in progress).